RESEARCH NOTES: The Body Keeps the Score Part 1

A., Van der Kolk Bessel. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Books, 2015.

While I had casually read this book over the course of the summer, the first thing I wanted to tackle was creating in-depth research notes, divided by topic, for each section of this 5 part book. The first section, The Rediscovery of Trauma, acts as a precursor to the rest of the book, explaining the history of PTSD as a diagnose-able entity, and laying the foundation for topics to be covered in the rest of book.

On the history side, the book explains how PTSD grew into being out of the realization that traumatized individuals displayed an expansive set of symptoms that were often misdiagnosed as other mental illnesses. Unsurprisingly, the field started with Veterans, specifically returning from Vietnam, and later included those with trauma from rape and other areas of life who all displayed similar issues.

Van der Kolk sketches out the various aspects of PTSD that will be covered in the rest of the book, and my following notes will point out things I intend to keep in mind as I work on my own project, areas that I see great overlap with my current work, and some instances of anecdotes or questions that relate to my own experience with PTSD. This is not intended to be a formal paper, or a substitute for reading the book.

NOTES FROM THE TEXT

Methods & Avenues for combating Post Traumatic Stress:

1. Top Down - talking, connection, communication & processing memories

2. Taking medication to help imbalances in brain chemistry

3. Bottom Up - allowing body to have visceral experiences to contradict helplessness, rage & collapse that result from trauma.

Not every method will work for every individual - its about finding your own combination.

Psychopharmacology, as a science, is a science devoted to creating drugs that help balance brain chemistry. While the pills, such as Prozac were shown, in double blind studies, to be 5x more effective than therapy alone, both methods, together are preferable in most situations. However, it was also found that while Prozac and other drugs worked significantly better than the Placebo effect for non-combat PTSD patients, it had no effect on veterans suffering from PTSD.

While the Brain Disease Model, which treats PTSD purely as an imbalance of hormones in the brain, has proven very effective in terms of treating PTSD with drugs, Van der Kolk aggressively wants his readers not to overlook what he refers to as Four Fundamental truths:

1. Our capacity to destroy is matched by our ability to heal each other.

2. Language has the power to change ourselves through communication and relationships with other people

3. We can regulate our own physiology through breath, movement & touch

4. We can change the social conditions we exist in to create environments where those with PTSD can thrive.

Trauma as Fragments & Memory

"That's what trauma does - it interrupts the plot" - Jessica Stern Denial: A Memoir of Terror

Hallucinations, auditory experiences and feelings are not fully narrative experiences but are fragmented memories of real experiences. I should be considering non-linear events for how the story unfolds in my VR world.

These fragmentary passages should eventually tell the narrative and elicit the desired emotional response without resorting to a true cinematic chronological experience.

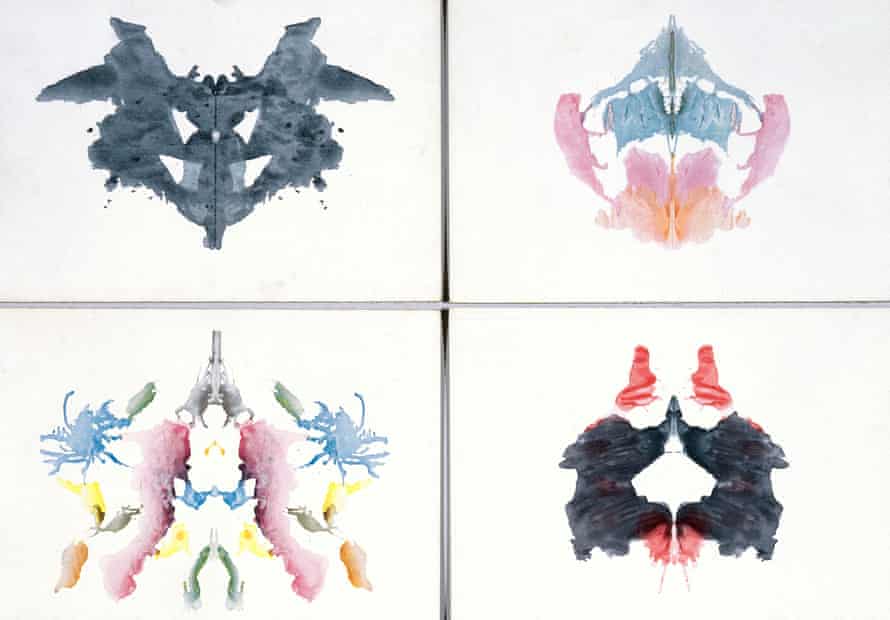

Rorschach Tests

Rorschach ink blots are used to observe how people construct mental images, and they appear to manifest in trauma victims imaginations as representative of their trauma. While black and white ink blot tests are well known, I am more intrigued by the concept of Color-shock. Color-shock are inkblots that use color and can illicit vivid responses.

The varying reactions seem to tell something about how the patients brain is processing. In tests, control groups tended to make up stories about what they see in each ink blot - a butterfly or something unrelated. Those with trauma had a tendency to relate the images they see back to their own history with trauma, building mental images related to their experiences. Of note, however, were people who had experienced trauma yet saw nothing but ink. This is troublesome as it ignores normal human stimuli to create a mental image or meaning in the abstract. In this sense, trauma can keep your mind from playing and lead to loss of mental flexibility & creativity.

If I am being honest, I have trouble with the concept of Rorschach tests, as they seem, to me, like a pseudoscience. For the purposes of my project, unless I get new ideas and focus with them, I don't know how/if I would use them, if for no other reason than I feel like they have become an unfortunate shorthand for evidence that a person is "crazy" in media.

Physicality

Van der Kolk asserts that physical experience and physicality can help someone suffering from Post Traumatic Stress by actively contradicting "the helplessness, rage & collapse that are a part of trauma" p. 4

This whole idea, that physical experience is an important part of the trauma healing process is, in many ways, the crux of my Thesis project, if not in a literal healing sense, then definitely in how it will be artistically presented. Much of my current artistic process in the piece will be learning to break free from the looping landscape of the cave.

Because of how physical experience can be wrapped up in undoing triggers, they can also make them worse. The book describes a scenario where a rape-trauma patient can be triggered by others ganging up to help her. The physical act of being grabbed and force fed medicine harked back to her trauma and made her symptoms worse, despite the goal of helping her. While this is not necessarily something I want to replicate exactly, at the very least it is something I need to keep in mind when creating the most ethical version of this game.

Symptoms

Addiction (to/because of) Trauma

Many traumatized people resort to substance abuse &/or self harm to block out the unbearable pain of trauma: And yet there seems to be an addiction to trauma itself.

Why do we keep coming back to our trauma? When performing group therapy on Vietnam Veterans, Van der Kolk found that many times his trauma patients felt the most alive when discussing their own trauma.

"Somehow the very event that caused them so much pain had also become their sole source of meaning. They felt fully alive only when they were revisiting their traumatic past" (p.18)

These veterans were gaining relief from the telling of the story, the admission of what they had done and what had happened, but not from the rebuilding process that they needed in order to move past their trauma. In Van der Kolk's experience, helping victims talk and describe their trauma is meaningful but not enough to combat the explosive rage, shutdown and other symptoms they experience.

That still is not enough to explain why we seemingly want to relive our trauma sometimes.

"Many traumatized people seem to seek out experiences that would repel most of us... [they] complain about a vague sense of emptiness and boredom when they are not angry, in duress, or involved in some dangerous activity" (p. 31).

To me this quote begins to describe the core concept I wish to work with: Looping. One of the most fascinating sections of Part I of this book has to do with what Freud refers to as the "Compulsion to Repeat" (p.32). According to Freud, these reenactments of trauma are unconscious attempts to gain control over a painful situation. At the time, he believed that this repetition could lead to mastery and resolution of trauma. In many ways, this logical train of thought is similar to what I tell myself whenever I start performing looping behaviors: If I can just understand what happened, if I can just relive the experience, see where something when wrong, I will be able to justify it, fix it, come to terms with it.

But that is a lie. Freud's theory is demonstrably false: Repetition (or looping) only leads to pain and self hatred, even when it is done in the course of therapy.

Essentially, what happens when we re-experience our trauma in this way is that the experience slowly shifts from a painful experience to an attractor, a thing that draws or motivates us. Attractors work like a drug addiction. We start to crave the this repetition as an activity and start to experience withdrawal symptoms when it is not there. We become more concerned with fixing our withdrawal than with the pain we experience from the trauma itself.

One study Van der Kolk performed on Vietnam Veterans showed that, when viewing graphic scenes from Platoon (1986) participants were able to keep their arms in icy water for 30% longer than when they were shown unrelated clips from other films. What they found is that strong emotions can block pain receptors, and that the stress experienced in PTSD actually relieved anxiety and pain by releasing natural chemicals in the brain that are equal to 8mL of Morphine. This is the same level of morphine given in the ER for severe chest pain.

Cover Stories

One of the hardest parts about dealing with trauma is confronting shame about ones own behavior during a traumatic episode. Many trauma survivors create a cover story, or a "clean" version of events to help explain their reactions and responses.

When I had my skiing accident at 11 years old, one of the first things I did was to create a cover story to make my accident appear in the best light. Although I don't think anyone would have scolded me, I claimed, until around the age of 18 or 19 that I had lost control of my skis when I plummeted down two moguls and flew up the steps of a sundeck halfway up a trail at Ski Sundown in Connecticut. In reality, I was too good a skier to have lost control that way. The truth was, I was in control of my actions until the last ten seconds of my accident. The weeks before my accident I had seen snowboarders using the steps of the sundeck as a makeshift jump. They would start slightly up the hill, ride down and do a jump on the snow covered stairs, taking turns to show off. I wanted desperately to be like them. I had recently tried doing an official jump that had been set up towards the bottom of the mountain and had taken to it like a fish to water. The day of my accident I had seen the steps were free and clear with a fresh layer of powder on top of them. My biggest mistake that day was not fully thinking through my plan. Starting at the top of the mountain I tore down the center of the hill directly for those stairs. In mid air, I felt like I was flying. Upon landing, elated. It was only in the split seconds after I landed, when I realized I had maybe 20 feet to stop myself that I realized I had no exit strategy.

But that's not the story I told for at least 7 years. It was more palatable to say that I lost control, because to explain that I hadn't was to live with the shame of culpability. And who would want to place blame on an 11 year old who suddenly couldn't walk? No one ever even questioned my version of events. Years later, even when I did come clean with my lived experience, I have always been told by others that, because I was 11 at the time, none of it was my fault. This is one dissonance that is hard to shake, even now.

Emotional Numbness

The term "out of body experience" is never one that I personally have ever felt described what it was like for me to go through dis-associative episodes. Page 14 used a different phrase that resonated with me. Instead of describing it as if you were no longer in your own body, Van der Kolk uses a patients words to describe an emotional absence as if the "heart were frozen and [one is] living behind a glass wall." While I have experienced this rarely I remember vividly each time it has. The wall goes up and it is as if nothing anyone says or does can hurt you. Everything is analytical. Blunt. My own words become icy and abrupt. I can hear myself saying things that are callous, yet there is no emotional intent to be callous. For me at least it takes some kind of physical shock to break free from. I am fortunate that this has only happened a few times, and not in years.

In terms of my project, this glass wall is something that I would want to replicate somehow - in fact, the artificial boundaries that are set in place by a VR system could be a good way to visually set this up - an area that you cannot go to but can see; something you should be able to break out of but cannot.

Inescapable Shock

Of all the things described in the first section, the animal testing dogs for Inescapable Shock seemed the most morally dubious. In the experiments, dogs, locked in cages, were given electric shocks multiple times. On the last occasion, when the dogs were shocked again, the door to the cage was opened. The control dogs, who had never been shocked before, immediately ran away from the stimulus. The dogs who had endured shocks before did not even try, simply lying down and crying. They found that "the only way to teach the traumatized dogs to get off the electric grid... was to repeatedly drag them out of their cages so they could physically experience how to get away" from the electric shocks (p30-31).

One of the most important game play loops I am hoping to include in the ending of the game is to teach the player that in order to escape the labyrinth in Sam's mind, they must break the boundaries of play that they have been given - they must literally walk through the stone wall. Prior to reading this section of the book, I have never heard of inescapable shock. While this will require testing, I realize now that if I want players to realize they need to break free I will need to repeatedly drag them physically out of their mental cage - essentially training them, like the dogs, that they can, in fact, get away. The ethics of doing this at all, of course are somewhat dubious, but I will to find the right balance with willing participants, rather than electrocuted dogs.

*Note from this section: The same study also found that animals will return home, whether or not it is safe or scary.

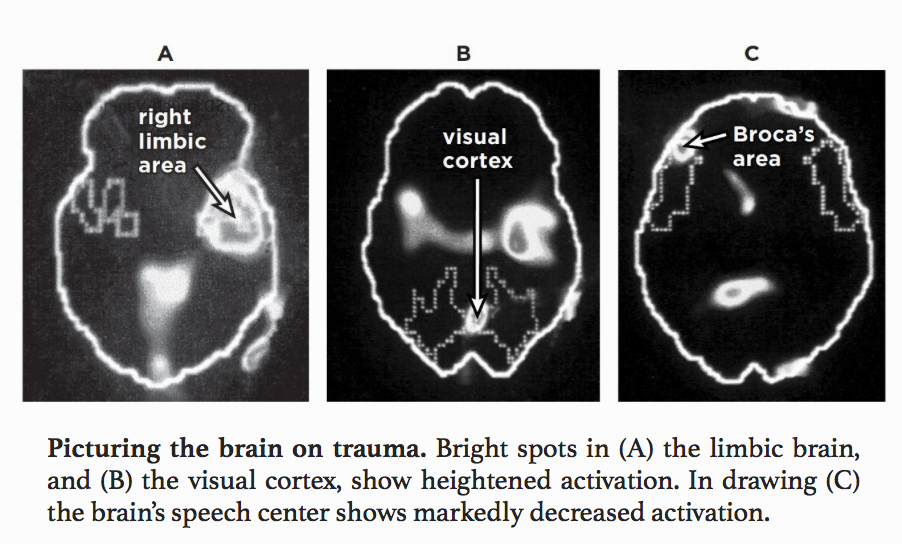

What's happening in the Brain

There is a portion of the brain, called Broca's Area, that is responsible for putting thoughts and feelings into words. Brain mapping technology actually shows that trauma can affect the brain in a similar manner to a stroke, shutting down one half of it at times. Under extreme conditions people will swear, scream, or completely shutdown.

Unprocessed fragments of trauma, such as sights, sounds, smells, and sensations can lead back into a trauma state through this closing off of Broca's area. This is, in part, how "triggers" work.

Right Brain vs Left Brain

Trauma activates the RIGHT brain, which is responsible for emotion, visual, spacial and tactile reasoning, and can even include methods of emotional communication, such as singing, dancing, and mimicry. At the same time it deactivates the LEFT brain, which is responsible for linguistics, sequential and analytical portions of our experience.

The shutting down of one side puts the traumatized individual in a state of fight or flight, and "the stress hormone in traumatized people takes much longer to return to baseline and can even spike quickly and disproportionately to mildly stressful stimuli" (p.41).

For me this disproportionate response relates to one of my more confusing triggers: when someone throws up near me, or if I feel like I need to throw up, I will immediately dissolve into a full blown fight or flight panic attack. I have no memories of throwing up at any point during my traumatic experience, yet the timeline suggests that this phobia began just after my skiing accident. Less than three months earlier, a student in my fifth grade class had run too fast during the mile run and blown chunks in the cafeteria. While I found it gross at the time, I had no emotional response - sympathetic or otherwise. Less than 3 months after my accident, I would go into full blown panic mode, going so far as to avoid the place where someone had thrown up for years. Even now, when I feel as though I am going to be sick, I get a flash fever, feel faint, and start shaking. I need to pace and will try to run away from those who feel stomach ill. I still do not know how these things are related, I only know that the timing is incredibly close to be considered a coincidence.

Denial is another possible response. The body registers a threat but the mind goes on as if nothing is wrong. However, that does not mean all is fine. The alarm does not stop just because the brain is not responding to the threat.

In many ways it is easier for people to talk about what was done to them and blame others - resorting to victimization and revenge than to actually express the reality of their internal experience.

Comments

Post a Comment